I'm obsessed with societal collapse.

Economic inequality? Cultural dissolution? Systemic poverty? Environmental degradation? Substance abuse? The depression epidemic? Racial unrest? Ideological polarization? These are the topics that keep me up at night.

Though: I'm not despondent about these. Not only is there hope — I think our society is even making important progress on some of these fronts, progress that goes largely unrecognized in the media.

But a good outcome isn't a foregone conclusion. We live in the middle of a story whose ending is still up for grabs. From my vantage point, it's reasonable to expect that we'll screw the whole thing up (and take half the biosphere with us) and, at the same time, reasonable to expect that we'll get society right (and create a world truly worthy of Homo sapiens).

And I'm obsessed about figuring out how we can move away from the bad ending, and toward the good one.

I say this because lately I've realized that almost no one knows this about me. (Not my friends; not even my wife! That was an intriguing conversation.)

And I say it because, at some level, my goals for this school — this new kind of school — are bound up with these questions.

Can a school — a new kind of school — help mend the world?

Not save the world, mind you. Save is all-or-nothing. Mend is a more realistic goal. Mend allows us to count half-steps, allows us to take pride in making improvements at any scale, allows us to work with others.

So: can it?

Three possible routes

Obviously, this question of "can a school mend the world?" is an old one. It's what launched the common school movement in the mid 1800s, what launched Dewey's Progressive movement in the early 1900s, what launched Maria Montessori's and Rudolf Steiner's schools in the mid-1900s.

I can count (at least) three routes that people have pursued as to how a type of schooling can do this. The first — ideological indoctrination — I think misguided (and entirely inappropriate for our school). The second two — developing skills and cultivating understanding — I think promising (and entirely fitting).

Route #1: Ideological take-over of society? Nah.

There's a famous essay — well, famous among historians of American education! — that advocates that schools be ideologically-charged: that they communicate the true view of the world and radicalize the students, who will then go on to launch the revolution that will change society.

(It's funny: the author I'm thinking of was a Communist, but what I just wrote could equally well describe any number of Republican or Democratic writers currently writing about education.)

The author was George Counts, a previous partner of John Dewey who, in the midst of the Great Depression penned the pamphlet "Dare the School Build a New Social Order?"

I love the chutzpah of the pamphlet. Heck, I love the chutzpah of just the title! (I bet George Counts' wife knew where he stood on mending the world!)

It's a short piece. If you haven't read it before, and have yet to fulfill your doctor's daily recommended dosage of fiery midcentury call-to-revolution rhetoric, can I suggest you take a skim through it?

Counts argues that schools should help bring about the socialist revolution:

If Progressive Education is to be genuinely progressive, it must... face squarely and courageously every social issue, come to grips with life in all its stark reality, establish an organic relation with the community, develop a realistic and comprehensive theory of welfare, fashion a compelling and challenging vision of human destiny, and become less frightened than it is today at the bogies of imposition and indoctrination.

This is the moment I probably should make something clear: George Counts was a Communist, and I'm not. (Though, oddly, I'm wearing this Communist Party t-shirt right now! In my defense, it was still dark when I picked my clothes this morning.)

George Counts, of course, failed in his attempt to make the teaching profession an extension of the Communist Party. And in retrospect, it's almost impossible to imagine he could have succeeded. Politics follows Newton's Third Law of Motion:

For any action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.

If well-meaning people on the Left try to bend schools to their will, then well-meaning people on the Right will step in to thwart them. And if well-meaning people on the Right try to do the same, then well-meaning people on the Left will step in.

George Counts' mistake was thinking that the schools could stand outside the rest of American society — that they could influence without being influenced (except by him!).

Mending the world by ideologically charging the schools: a losing game.

Route #2: Building skills? Yes.

But there are other routes to mending the world: one is by building crazy-mad skill.

I'm teaching a high school course in moral economics this year, and this week we've talked about human capital. "Human capital" is a term from economics, invented when economists started taking seriously that the resources that lead to economic well-being aren't just oil and machines and large stacks of bills: they include the grand sum of skill, natural talent, knowledge, experience, intelligence, judgement, and wisdom that reside inside people and contribute to their ability to make a living.

Human capital, to be clear, is a very expansive idea. Sci-fi author Robert Heinlein once wrote:

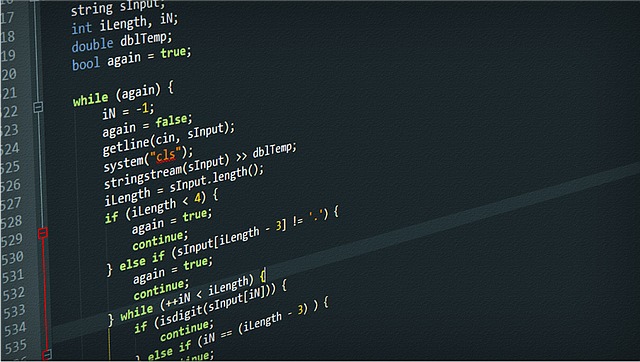

A human being should be able to change a diaper, plan an invasion, butcher a hog, conn a ship, design a building, write a sonnet, balance accounts, build a wall, set a bone, comfort the dying, take orders, give orders, cooperate, act alone, solve equations, analyze a new problem, pitch manure, program a computer, cook a tasty meal, fight efficiently, die gallantly. Specialization is for insects.

All of these, even, fit cheerfully within "human capital." (In fact, one of the primary criticisms of the concept is that it's too inclusive, but that's a different topic.)

Why do we care about this? Because human capital is one of answers to the question "why are some people more successful than others?"

Charles Wheelan, a professor of public policy at Dartmouth, writes in Naked Economics:

True, people are poor in America because they cannot find good jobs. But that is the symptom, not the illness. The underlying problem is a lack of skills, or human capital. The poverty rate for high school dropouts in America is 12 times the poverty rate for college graduates. Why is India one of the poorest countries in the world? Primarily because 35 percent of the population is illiterate.

Now: this isn't the whole story. Poverty is a complex beast, and it has more causes than a dearth of human capital: systematic racism, classism, sexism, and so on. But human capital explains a crucial part of what holds some people back (and allows others to leap ahead).

The wonderful thing, of course, is that schools do provide human capital: reading, writing, math, and so on. The terrible thing is that they seem to not do it particularly well.

Take reading. Diane McGuinness unpacks a research finding, in Why Our Children Can't Read (And What We Can Do about It):

about 17 percent of working adults, thirty-three million people, are both well educated and sufficiently literate to work effectively in a complex technological world. We are dooming the vast majority of Americans to be second-class citizens.

And E.D. Hirsch writes, in The Knowledge Deficit:

Reading proficiency… is rightly called "the new civil rights frontier."

There's a defensiveness that can pop up when people criticize schools. To be clear, I'm not criticizing public schools in particular: it's been demonstrated that private schools don't do a much better job.

There's also a defensiveness that can pop up when people suggest that people in poverty lack skills — the idea can appear to people as "blaming the victim." But does anyone really want to argue that children born into intergenerational poverty wouldn't benefit from reading much better, from excelling at math and science and computer programming and everything else?

A new kind of schooling can deliver human capital. Heck, we can develop superpowers — recall that this is Big Goal Number Two of our school! And we can do so without stirring up the ire of the political Left and Right, the way ideologically-charge interventions do.

We can empower people — especially marginalized populations. We can help people read well, write well, and think well. And by doing so, we can help mend the world.

Charles Wheelan again, citing Marvin Zonis:

Complexity will be the hallmark of our age. The demand everywhere will be for ever higher levels of human capital. The countries that get that right, the companies that understand how to mobilize and apply that human capital, and the schools that produce it… will be the big winners of our age.

I'm not concerned with our schools being "winners" of our age. I'm obsessed with cultivating children and adolescents who have the capacity to win for themselves, and for others.

And we can do this.

Route #3: Expanding understanding? Oh yes.

There's one more route, I think, that a new kind of school can take to helping mend the world: expanding comprehension about how the world really works.

On this blog, I've been concentrating on describing our vision for elementary school, because that's what we'll be opening with in 2016. Our high school program is a decade out — we'll be growing the school organically with our opening classes of kids.

But boy, am I excited to be starting a high school.

I'm a high school teacher, and I love my job precisely because I get to spend my days peeking into how the world hangs together. A stranger, looking over a list of the social science courses I teach, might be confused —

- Moral Economics

- Evil

- Happiness

- Philosophical Worldviews

- World Religions

- Political Ideologies

- The Next 50 Years

- Ancient History

- Moral Controversies in American History

The thing that connects them is my obsession with how society works. Why can we explore space but still have poverty? Why do some people behave horrifically to others? What is the good life? How do ideas drive society? Where is technology taking us? Where do we come from? And so on.

Many students don't get the opportunity to deliberate on these compelling questions in school. Most schools aren't designed to reflect on issues like these every single day. Most schools aren't designed to help students ask probing questions, identify and overcome their biases, and develop hard-won wisdom.

Ours can be! (In fact, this is our school's Big Idea Number Three.)

The thing to keep in mind is that mending the world is possible. We know that, because we've seen it.

Steven Pinker's recent book on how some things (especially rates of violence) really have been getting better — The Better Angels of Our Nature — helped convince me of this. From that he wrote a short essay, "A Two-Minute Case for Optimism," that appeared on (and I love this) Chipolte bags. The essay concludes:

“Better” does not mean “perfect.” Too many people still live in misery and die prematurely, and new challenges, such as climate change, confront us. But measuring the progress we’ve made in the past emboldens us to strive for more in the future. Problems that look hopeless may not be; human ingenuity can chip away at them. We will never have a perfect world, but it’s not romantic or naïve to work toward a better one.

We can have a better world. To some degree, every school everywhere — every teacher who teaches — is already creating this world.

Our school can be part of that effort.

Also, it seems like the school as a whole would learn a singular language together (or 2+ time permitting). Do you see the group learning together as important? For instance, would it be detrimental for half of the kids to learn German while the other half learns Korean?